Solid State Batteries

What Is a Solid-State Battery?

A solid-state battery (SSB) is a battery technology that uses a solid electrolyte instead of the flammable liquid electrolyte used in conventional lithium-ion batteries. Similar to conventional lithium-ion cells, lithium ions migrate from the cathode to the anode during charging and reverse direction during discharge. However, replacing liquid electrolyte by solid electrolyte fundamentally changes how Li-ion moves between the electrodes, electrodes - electrolyte interaction, and the battery’s response to external factors such as heat and mechanical stress.

Solid-state batteries offer a promising pathway towards higher energy density, improved safety, and longer cycle life. These attributes make them particularly attractive for high energy applications such as electric vehicles, where extended driving range and safety are critical, as well as for aerospace and defense systems.

Despite their potential, solid-state batteries still face several limitations, including high interfacial resistance, mechanical degradation during cycling, and increased materials and manufacturing complexities. As a result, large-scale commercial deployment remains limited.

TLDR: Solid-state batteries don’t magically fix lithium-ion: they change where the pain lives. (Because you traded flammable liquid problems for interface, pressure, and manufacturing hell.)

The future of batteries may be solid, but nothing about the work to get there is simple, fast, or forgiving.

Key Components

Cathode Materials

Solid-state batteries generally use already established cathode materials for lithium-ion technology, including layered transition metal oxides such as NMC and NCA, as well as lithium iron phosphate (LFP). Next generation cathodes such as sulfur, Li-rich cathodes are also compatible with SSB. The main challenge lies in integrating these materials with a solid electrolyte. Unlike liquid electrolytes, solid electrolytes cannot infiltrate conventional porous electrode structures resulting in high interfacial resistance. To address this issue, composite cathodes combining active material, solid electrolyte, and conductive additives to ensure continuous pathways for both ions and electrons are commonly used. Managing interfacial resistance and chemical stability within these composites remains a central research focus.

Anode Materials

One of the most compelling advantages of solid-state batteries is their compatibility with lithium metal anodes. Lithium metal offers an extremely high theoretical capacity, enabling significantly higher energy density compared to graphite anodes used in conventional lithium-ion cells. The interface between lithium metal and the solid electrolyte is unstable, and repeated plating and stripping of lithium can lead to void formation, loss of contact and increased resistance. Maintaining intimate and stable contact at this interface, despite volume changes during cycling, is essential for long-term performance.

Lithium metal anodes promise huge gains on paper, but in solid-state cells they expose every weakness in your interface design.

Solid Electrolyte

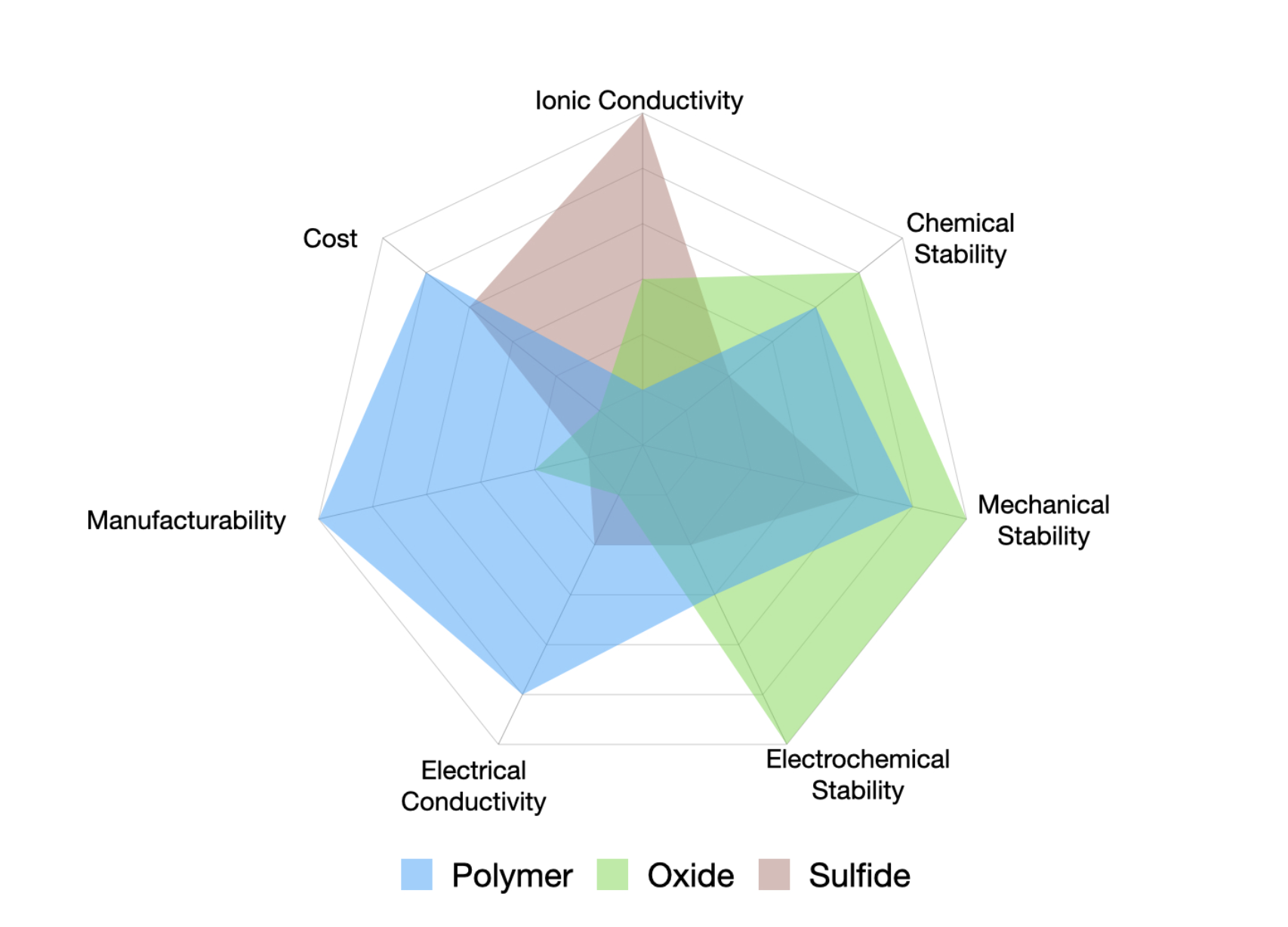

The solid electrolyte is the defining component of SSBs. Its role is to transport lithium ions efficiently between the electrodes while remaining chemically stable and mechanically robust. Broadly, solid electrolytes can be classified into three main categories: polymer-based, oxide-based, and sulfide-based electrolytes.

Oxide-Based electrolytes: There are different types of oxide-based solid electrolytes based on the composition. LiPON, NASICON, GARNET and perovskite are the most popular categories. Oxide-based electrolytes have ionic conductivity in the range of 1 mS/cm which is significantly lower than the liquid electrolytes which require the cells to operate at elevated temperature. Oxide-based electrolytes such as garnets are valued for their excellent electrochemical stability, however their stiffness often leads to poor contact with electrodes and high susceptibility to dendrite formation.

Sulfide-Based electrolytes: Sulfide electrolytes include glassy and glass-ceramic Li–P–S (LPS) systems, argyrodite-type materials (Li₆PS₅X, where X is halogens), thio-LISICONs, and Li₁₀GeP₂S₁₂ (LGPS). Among these, LGPS and argyrodite materials, offer high ionic conductivity 10-2 S/cm comparable to that of liquid electrolytes and form good interfacial contact due to their softer nature. However, their poor electrochemical chemical stability results in parasitic reactions forming resistive layers. Additionally, sulfide electrolytes are highly sensitive to moisture and hence require processing in inert atmospheres to prevent degradation and release of toxic H₂S gas, making processing and handling more complex and expensive.

Polymer-Based Electrolytes: Polymer bases SEs are composed of Li-ion salt in a high molecular weight polymer matrix. Polymer based solid electrolytes have poor ionic conductivity at room temperature, often requiring elevated (~ 60°C) operating temperature. Their mechanical flexibility provides robust mechanical stability and enables effective interfacial contact. Polymer-based solid electrolytes represent the most commercially mature class of solid-state electrolytes due to their relatively simple processing, established manufacturing routes, and compatibility with existing battery technologies and are already being deployed in early-stage applications.

If your solid electrolyte has great ionic conductivity in a paper, but needs 20 MPa of stack pressure to work, congratulations: you built a lab demo, not a product.

Figure 1: Comparison of the key properties of different types of solid electrolytes.

Manufacturing Considerations

While solid-state batteries offer clear performance and safety advantages, they also introduce new manufacturing challenges. Many solid electrolytes require strict moisture control, and high stack pressures are often necessary to maintain stable interfaces between electrode and electrolyte layers. In addition, current solid-state designs are not fully compatible with existing roll-to-roll lithium-ion manufacturing processes. Although laboratory-scale results are promising, scaling these technologies to cost-effective, high-volume production remains a major hurdle. Manufacturing challenges vary considerably across electrolyte classes.

Polymer electrolytes: Manufacturing is relatively simple, with mature and scalable industrial processes already established, particularly for thin-film production.

Oxide electrolytes: Processing is challenging due to the hard and brittle nature of the materials. Achieving dense, low–grain-boundary-resistance layers requires high-temperature sintering, making fabrication complex. At present, wet-chemical routes dominate, and scalable large-volume manufacturing remains an active research challenge.

Sulfide electrolytes: Production is complex because materials are highly sensitive to moisture and must be handled in inert atmospheres to prevent degradation and toxic H₂S formation. Although fabrication at relatively low temperatures is possible, processing complexity and environmental control requirements significantly complicate scale-up.

Bottom Line

Solid-state batteries are not yet a direct replacement for today’s lithium-ion technology, but they represent a meaningful step forward in battery design. Continued advances in materials engineering, interface control, and scalable manufacturing will determine how quickly solid-state batteries transition from the laboratory to widespread commercial use.

Solid-state batteries will get here, but not on press releases alone. Interfaces, pressure, and manufacturing decide the timeline.

References

Huang et al., ACS Symposium Series Vol. 1413, 2022. DOI: 10.1021/bk-2022-1413.ch001

Irfan et al., ACS Symposium Series Vol. 1413, 2022. DOI: 10.1021/bk-2022-1413.ch008

Wang et al., ACS Symposium Series Vol. 1413, 2022. DOI: 10.1021/bk-2022-1413.ch012

Rosero-Navarro et al., ACS Symposium Series Vol. 1413, 2022. DOI: 10.1021/bk-2022-1413.ch013